For Jews, the Medieval Era—according to Ivan Marcus--is defined by conditions “of corporate subordination to a dominant monotheistic and hence, exclusivistic religious majority in power over them.” This definition was abstract and unwieldy when we first read it several weeks ago. But by this time in the semester, it begins to come into focus

In recent sessions we have explored what it means for a society to be divided up into corporate groups. Likewise, we have focused on the implications of belonging to the Jewish subordinate minority group within such a social structure.

In the 1920s, Jewish historian Salo Baron called for a “break” with the “lachrymose” approach to the study of Jewish history. Indeed, the Middle Ages were years of great cultural creativity for the Jews. Yet, it is difficult to get away from the lachrymose part of the story when reading the Muslim and Christian texts that outlined how Jews were to be treated.

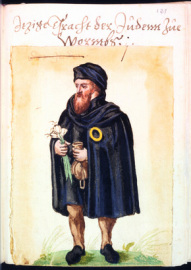

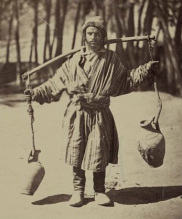

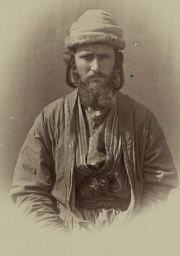

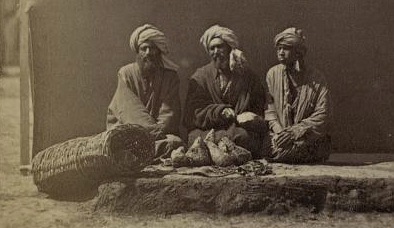

The Muslim “Pact of Umar” and Augustine’s Christian “Doctrine of Witness” both grant Jews the right to practice their religion freely, and provide them with the promise of security of body and property. In return for these conditions, however, the Jews were required to accept upon themselves humiliating disabilities. Furthermore, they were to be marked (through their garb) to ensure that they not pass for anything other than Jewish.

Exactly how influential and pervasive were these documents? The pact of Umar was written (supposedly) in the 7th century, and the Doctrine of Witness was written in the fourth. Did they continue to invoked? Where, and for how long?

Theologian Rosemary Reuther argues that the birth of Christianity was intrinsically linked to the assertion of the Jews’ reprobate status. One hinged upon the other. In her words, “anti-Judaism was the negative side of the Christian claim that Jesus was Christ.”

This proposition is well expressed by Augustine in his interpretation of the story of Cain and Abel. Cain killed his brother Abel, just as the Jews killed Jesus. Cain is exiled from the Garden of Eden, and forever doomed to a life of groaning and wandering. His fate as a perpetually homeless outsider serves as a reminder of his sin and degraded status (what a troubling metaphor!). Yet, he is to be kept alive for “whosoever shall kill Cain, vengeance shall be taken on his sevenfold.” So too, Augustine teaches, “preservation of the Jews” is to serve as “proof to believing Christians of the subjection merited by those who… put the Lord to death.”

Reuther views Augustine’s theological proposition as the “foundation of the demonic view of the Jews” which in turn, “fanned the flames of popular hatred,” and “laid the inferiorization of the civic and personal status of the Jews in Christian society.” For Ruether, theology—as explicated by the Church fathers--is the root cause of Jewish persecution during the Middle Ages and into the modern era.

In his work, “Under Crescent and Cross,” Mark Cohen offers a more dynamic and complex analysis of Jewish persecution (in both Christian and Muslim society). He takes into account social, political and economic factors in addition to theological ones – without privileging one over another. Regardless of how we view the causes, however, one thing is certain: Jews suffered in the Middle Ages on account of their Jewishness. In our next class we will look at the cluster of allegations leveled against them in Christian Europe (desecration of the host, the poisoning of wells, and ritual murder) which led to persecution and massacre.

In the second half of class we will move away from this gloomy aspect of history, to address the strategies Jews used – in the Muslim world as well as the Christian one – to create lives of dignity in spite of their degradation.

In recent sessions we have explored what it means for a society to be divided up into corporate groups. Likewise, we have focused on the implications of belonging to the Jewish subordinate minority group within such a social structure.

In the 1920s, Jewish historian Salo Baron called for a “break” with the “lachrymose” approach to the study of Jewish history. Indeed, the Middle Ages were years of great cultural creativity for the Jews. Yet, it is difficult to get away from the lachrymose part of the story when reading the Muslim and Christian texts that outlined how Jews were to be treated.

The Muslim “Pact of Umar” and Augustine’s Christian “Doctrine of Witness” both grant Jews the right to practice their religion freely, and provide them with the promise of security of body and property. In return for these conditions, however, the Jews were required to accept upon themselves humiliating disabilities. Furthermore, they were to be marked (through their garb) to ensure that they not pass for anything other than Jewish.

Exactly how influential and pervasive were these documents? The pact of Umar was written (supposedly) in the 7th century, and the Doctrine of Witness was written in the fourth. Did they continue to invoked? Where, and for how long?

Theologian Rosemary Reuther argues that the birth of Christianity was intrinsically linked to the assertion of the Jews’ reprobate status. One hinged upon the other. In her words, “anti-Judaism was the negative side of the Christian claim that Jesus was Christ.”

This proposition is well expressed by Augustine in his interpretation of the story of Cain and Abel. Cain killed his brother Abel, just as the Jews killed Jesus. Cain is exiled from the Garden of Eden, and forever doomed to a life of groaning and wandering. His fate as a perpetually homeless outsider serves as a reminder of his sin and degraded status (what a troubling metaphor!). Yet, he is to be kept alive for “whosoever shall kill Cain, vengeance shall be taken on his sevenfold.” So too, Augustine teaches, “preservation of the Jews” is to serve as “proof to believing Christians of the subjection merited by those who… put the Lord to death.”

Reuther views Augustine’s theological proposition as the “foundation of the demonic view of the Jews” which in turn, “fanned the flames of popular hatred,” and “laid the inferiorization of the civic and personal status of the Jews in Christian society.” For Ruether, theology—as explicated by the Church fathers--is the root cause of Jewish persecution during the Middle Ages and into the modern era.

In his work, “Under Crescent and Cross,” Mark Cohen offers a more dynamic and complex analysis of Jewish persecution (in both Christian and Muslim society). He takes into account social, political and economic factors in addition to theological ones – without privileging one over another. Regardless of how we view the causes, however, one thing is certain: Jews suffered in the Middle Ages on account of their Jewishness. In our next class we will look at the cluster of allegations leveled against them in Christian Europe (desecration of the host, the poisoning of wells, and ritual murder) which led to persecution and massacre.

In the second half of class we will move away from this gloomy aspect of history, to address the strategies Jews used – in the Muslim world as well as the Christian one – to create lives of dignity in spite of their degradation.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed