How did the Jews fare under Islamic rule? It is tempting to answer this question by pointing to the Pact of Umar. This document, supposedly penned in the 7th century, was issued and re-issued throughout history, and across much of the Muslim world. It lists the humiliating conditions by which Jews (and Christians) were to abide in exchange for security of property and body, and freedom to practice their religion.

Jews were permitted to pray in synagogues, but they could not rebuild or restore those in need of repair. They could hold religious ceremonies as long as they were not were not conducted in a loud or extravagant manner. They were required to wear clothing and take names that marked them as different. They could bear no weapons. They could sell no wine. And they were to comport themselves in a subservient manner; their homes were to be lower than their Muslim neighbors, they were not to ride in saddles, and they were to rise if a Muslim wished to be seated.

But these legal stipulations reveal only part of the story. Jewish historian Mark Cohen explains that “economic, political and social factors acted….as a counterweight to the fundamental theological hostility towards the religion.” Cohen uses the wide-angle lens of political, economic and social analysis to assess the condition of the Jews under Muslim rule in the broadest strokes.

To understand how Jews lived under Muslim rule, it is also useful to do a close analysis of particular places at particular points in time. I recently learned of a trove of photographs taken in Muslim Central Asia at the end of the 1860s. This historic record is currently housed at the Library of Congress (and available on-line here). Put together by Russian authorities, it provides a panoramic view of society just before colonialism utterly transformed the society.

I’ll be speaking about this oeuvre at the conference of the Association of Jewish Studies this December. In the meantime, here are a few notes:

Among the 1,200 images that appear in Turkestan Album, most are of the region’s Muslim population. Some 40 or so, however, are of the Jewish minority. They provide a very interesting window into their life as dhimmi. In this brief essay, I’ll look at the Jews’ dress, with a particular focus on men’s hair and headgear.

Jews were permitted to pray in synagogues, but they could not rebuild or restore those in need of repair. They could hold religious ceremonies as long as they were not were not conducted in a loud or extravagant manner. They were required to wear clothing and take names that marked them as different. They could bear no weapons. They could sell no wine. And they were to comport themselves in a subservient manner; their homes were to be lower than their Muslim neighbors, they were not to ride in saddles, and they were to rise if a Muslim wished to be seated.

But these legal stipulations reveal only part of the story. Jewish historian Mark Cohen explains that “economic, political and social factors acted….as a counterweight to the fundamental theological hostility towards the religion.” Cohen uses the wide-angle lens of political, economic and social analysis to assess the condition of the Jews under Muslim rule in the broadest strokes.

To understand how Jews lived under Muslim rule, it is also useful to do a close analysis of particular places at particular points in time. I recently learned of a trove of photographs taken in Muslim Central Asia at the end of the 1860s. This historic record is currently housed at the Library of Congress (and available on-line here). Put together by Russian authorities, it provides a panoramic view of society just before colonialism utterly transformed the society.

I’ll be speaking about this oeuvre at the conference of the Association of Jewish Studies this December. In the meantime, here are a few notes:

Among the 1,200 images that appear in Turkestan Album, most are of the region’s Muslim population. Some 40 or so, however, are of the Jewish minority. They provide a very interesting window into their life as dhimmi. In this brief essay, I’ll look at the Jews’ dress, with a particular focus on men’s hair and headgear.

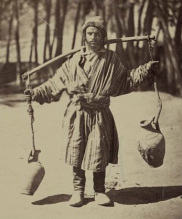

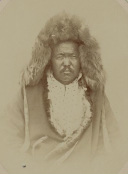

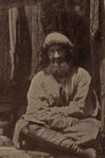

This water carrier is identifiably Jewish. Ephraim Neumark who traveled to Central Asia in the 1880s, writes in his travelogue that Jewish men were permitted to wear only one sort of cap, referred to as a “tilpak.” Neumark describes the cap as “made of sheepskin.” Others have described it as “conical shaped” and fur-trimmed, which all fit the description of the hat worn here by our friend the water-carrier.

His side-locks also mark him as Jewish. The Biblical injunction that a Jewish man may not cut the corners of his hair has led to the sporting of peyot – sidelocks - among Jewish men in various parts of the globe. It is worth noting that Alexander Burnes, who traveled to Central Asia in the 1830s, describes this hair-arrangement as a fashion statement rather than as Jewish religious prescription. He writes, “Their features are set off by ringlets of beautiful hair hanging over their cheeks and neck.” Rather than a mark of difference imposed by the Muslims, this style is a self-identifier chosen by Jews of their own volition.

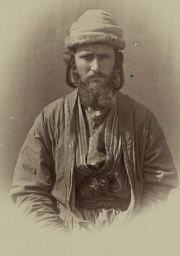

The photo of a Jewish man, below, matches these same descriptors.

His side-locks also mark him as Jewish. The Biblical injunction that a Jewish man may not cut the corners of his hair has led to the sporting of peyot – sidelocks - among Jewish men in various parts of the globe. It is worth noting that Alexander Burnes, who traveled to Central Asia in the 1830s, describes this hair-arrangement as a fashion statement rather than as Jewish religious prescription. He writes, “Their features are set off by ringlets of beautiful hair hanging over their cheeks and neck.” Rather than a mark of difference imposed by the Muslims, this style is a self-identifier chosen by Jews of their own volition.

The photo of a Jewish man, below, matches these same descriptors.

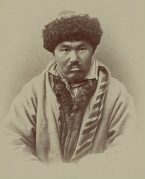

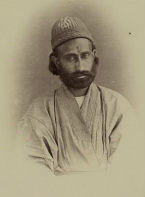

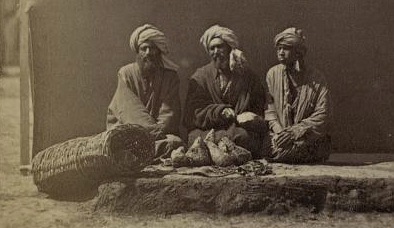

Were Jews the only ones whose headgear and hairstyle marked them as different? A comparison to the portraits of other men (which also appear in Turkestan Album) indicates that each group had its own distinctive headgear. Here are a few noteworthy images.

A Kazakh Man An Indian Man A Kyrgyz Man

A Kazakh Man An Indian Man A Kyrgyz Man

From the perspective of 21st century America, this fashion variety may be mistaken for celebration of ethnic difference. And, one might assume that the Jews were just one of many groups who enlivened the social landscape through their own special garb.

Neumark’s travelogue cautions us against such a view. In addition to describing the tilpak hat that Jewish men did wear, he also describes what Jewish men were not allowed to wear. Unlike the Muslims—he explains—Jews were not allowed to wear turbans. In this social landscape, the turban was a sign of masculine respectability.

Neumark’s travelogue cautions us against such a view. In addition to describing the tilpak hat that Jewish men did wear, he also describes what Jewish men were not allowed to wear. Unlike the Muslims—he explains—Jews were not allowed to wear turbans. In this social landscape, the turban was a sign of masculine respectability.

To the left, for example, is a picture of a Muslim judge. One did not need to occupy an honorable position to wear a turban (although one that was wide and bulky, like this judge’s, was the mark of status). Below we see a few simpler men sporting turbans. The photographer who took their shot in the marketplace may have bought lunch from them. He labeled them “Vendors of Boiled Giblets." Bon appetite!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed