If eyes are a window into an individual's soul, perhaps windows can provide a view into the soul of a congregation.

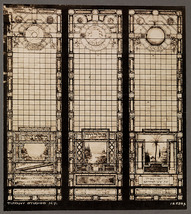

A highlight of our class tour of the Temple Tiferet Israel's new building was viewing the 12 glass windows inside the building's new chapel, in addition to the three “warrior windows” just outside the chapel. All were commissioned by Rabbi Abba Hillel Silver just after World War II, in memory of the 22 Temple members who fell in the war, and in honor of the other 776 who served.

A highlight of our class tour of the Temple Tiferet Israel's new building was viewing the 12 glass windows inside the building's new chapel, in addition to the three “warrior windows” just outside the chapel. All were commissioned by Rabbi Abba Hillel Silver just after World War II, in memory of the 22 Temple members who fell in the war, and in honor of the other 776 who served.

The windows were originally created in the late 1940s, designed specifically for the congregation’s urban home, located in Cleveland's University Circle district (pictured to the left)

That building was recently gifted to Case Western Reserve University and turned into the Maltz Performing Arts Center.

In the meantime, the congregation has vacated this space, and moved into its newly re-furbished home in Beachwood. What about the windows? Would they come along?

That building was recently gifted to Case Western Reserve University and turned into the Maltz Performing Arts Center.

In the meantime, the congregation has vacated this space, and moved into its newly re-furbished home in Beachwood. What about the windows? Would they come along?

We know, of course, that they did! But the factors that went into making this decision are worth considering, because they open up some larger issues.

Here are some reasons offered for not moving them:

Here are some reasons offered for not moving them:

- Windows are integral to a building’s design. So, if they were to be removed, the holes left behind would have to patched.

- As windows, they have been exposed to the elements, and were in need of repair and restoration at the hands of experts. Was the project worth it?

- Moving the windows would also mean that the new space would have to be designed around them to accommodate their size, shape and style.

- Finally, the larger question of where such windows belong: Perhaps they are part of the building, rather than possessions of the congregation?

And below are some of the reasons for removing them from the building they occupied, and relocating them to the Temple Tiferet Israel’s newly refurbished and re-dedicated home in Beachwood (shown here in a schematic drawing to the left):

- Their stunning beauty, and the desire for them to adorn the new space

- The preservation of the memory of those members of the Temple who served as soldiers in World War II, and who fell.

- Their value. Designed by the artist Arthur Szyk makes them commodities.

- Finally, the feeling that the windows belong to the congregation (rather than to the building itself). For decades they hung in the intimate and well-used chapel, and came to be associated with prayer, community, and rites of passage. In this sense, they are viewed not only as beautiful artwork, but also as physical manifestations of the congregation’s essence.

Ultimately, they were moved and they now hang in their new space.

How are they doing there?

Interesting is that do not serve the same functional purpose as they did in their old space. They are no longer windows! The glass has been fully encased so that the artistry is protected from the elements. This means they do not let in natural light. Nor can be viewed from outside (except as frosted panels - see above). From the inside, they appear to be windows, but in fact, their details are visible only when they are electrically-illuminated from behind.

How are they doing there?

Interesting is that do not serve the same functional purpose as they did in their old space. They are no longer windows! The glass has been fully encased so that the artistry is protected from the elements. This means they do not let in natural light. Nor can be viewed from outside (except as frosted panels - see above). From the inside, they appear to be windows, but in fact, their details are visible only when they are electrically-illuminated from behind.

No longer windows, they are now solely objects d’art. Regardless, they continue to remind congregants of where they came from, of their history, and of the value their community places on sanctifying space through beauty.

For me, the story of the Temple’s Szyk windows highlights the important role that objects - material culture – play in defining community.

Looking towards next class: What are the implications of the tight connection between community-identity and material culture for shrinking congregations? What happens when a congregation becomes so small, that it can no longer maintain the facility that the congregants built decades before? When should a congregation unburden themselves of their belongings? And what should become of their things?

We'll be discussing these issues in our upcoming class, using the article here as entree into our conversation: “Perpetuating Disappearing Congregations” published in the Jerusalem Report, November, 2013.

Looking towards next class: What are the implications of the tight connection between community-identity and material culture for shrinking congregations? What happens when a congregation becomes so small, that it can no longer maintain the facility that the congregants built decades before? When should a congregation unburden themselves of their belongings? And what should become of their things?

We'll be discussing these issues in our upcoming class, using the article here as entree into our conversation: “Perpetuating Disappearing Congregations” published in the Jerusalem Report, November, 2013.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed