| | My second year teaching the Cleveland Jewish Arts and Culture Lab came to a close last night - with a stunning, warm and vibrant show! This year's theme was "Remembering and Forgetting." It was amazing to watch the artists work emerge over the months of our meetings together. My remarks are below: MEMORY ARTISTS: As I prepared to teaching this year's Jewish Arts and Culture Fellows, I conjured up a Jewish Museum of Memory Art, home to three imaginary galleries |

|

0 Comments

This afternoon - on the eve of 2018 - the remaining members of Temple Hadar Israel said goodbye to their congregation, which was founded (originally as Temple Tifereth Israel) almost 125 years ago. As the economy changed across the rust belt, the town's population dwindled, and most Jews moved away.

A few years ago, Sam Bernstine asked his fellow congregants, "Do you want a dignified end? Or do you want the last person alive to have to shut out the lights?" The group responded with thoughtful planning and responsible disbursement of their assets - with the help of Jewish Community Legacy Project. Today's respectful and soulful burial - for the few items they could not manage to give away - was their final act as a group. Join me for this exciting event! I've had a great few months working with the Jewish Arts and Culture Lab. The show brings together an amazing group of pieces (sculpture, poetry, illustration, song, painting and collage) - which respond to each other in really interesting and exciting ways. For the opening, this Tuesday night, I'll be sharing remarks about the intersections between Jewishness and Creative expression (where they fit easily and where the challenges lie), and I will draw together some of the exciting themes - related to BOUNDARIES - that run through the show’s disparate and dynamic pieces.

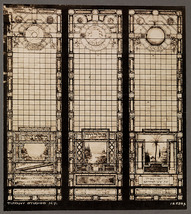

If eyes are a window into an individual's soul, perhaps windows can provide a view into the soul of a congregation. A highlight of our class tour of the Temple Tiferet Israel's new building was viewing the 12 glass windows inside the building's new chapel, in addition to the three “warrior windows” just outside the chapel. All were commissioned by Rabbi Abba Hillel Silver just after World War II, in memory of the 22 Temple members who fell in the war, and in honor of the other 776 who served.  The windows were originally created in the late 1940s, designed specifically for the congregation’s urban home, located in Cleveland's University Circle district (pictured to the left) That building was recently gifted to Case Western Reserve University and turned into the Maltz Performing Arts Center. In the meantime, the congregation has vacated this space, and moved into its newly re-furbished home in Beachwood. What about the windows? Would they come along? We know, of course, that they did! But the factors that went into making this decision are worth considering, because they open up some larger issues. Here are some reasons offered for not moving them:

And below are some of the reasons for removing them from the building they occupied, and relocating them to the Temple Tiferet Israel’s newly refurbished and re-dedicated home in Beachwood (shown here in a schematic drawing to the left):

Ultimately, they were moved and they now hang in their new space. How are they doing there? Interesting is that do not serve the same functional purpose as they did in their old space. They are no longer windows! The glass has been fully encased so that the artistry is protected from the elements. This means they do not let in natural light. Nor can be viewed from outside (except as frosted panels - see above). From the inside, they appear to be windows, but in fact, their details are visible only when they are electrically-illuminated from behind.  No longer windows, they are now solely objects d’art. Regardless, they continue to remind congregants of where they came from, of their history, and of the value their community places on sanctifying space through beauty. For me, the story of the Temple’s Szyk windows highlights the important role that objects - material culture – play in defining community.

Looking towards next class: What are the implications of the tight connection between community-identity and material culture for shrinking congregations? What happens when a congregation becomes so small, that it can no longer maintain the facility that the congregants built decades before? When should a congregation unburden themselves of their belongings? And what should become of their things? We'll be discussing these issues in our upcoming class, using the article here as entree into our conversation: “Perpetuating Disappearing Congregations” published in the Jerusalem Report, November, 2013.

We can ask similar questions about a collection (Who created the collection? Why? What purpose was the collection meant to serve? And how has its purpose or usefulness changed with age?) Upon whom does the responsibility fall to properly keep and transmit such information (if anyone)? In class, we did not come up with a good answer! THE “IDEAL CAREER” OF A COLLECTION We also followed the life story of the Horwitz collection (the bulk of which was transferred to the B’nai Brith museum in Washington DC, was later put into storage, and was finally transferred to the Skirball Museum in Cincinnati). We found this life story to fall short of the “ideal career” for such a collection. These are the qualities of a collection's “ideal career”:

END OF LIFE FOR A RITUAL OBJECT In our discussions about the various pieces in the Horwitz collection, we reached a dead-end when it came to the question: What is the ideal life-span for a Jewish ritual object? How should the end of its life be determined? And what should happen to it once it reaches the end of its life? Indeed there is cultural discomfort around disposing of Jewish ritual items (or dismantling a collection, a library, a set of synagogue possessions). When such scattering and disposal does occur, it is often with little fanfare, and without acknowledgement or reflection on what the object’s end-of-life signifies. TORAH SCROLL The Torah Scroll is particularly interesting because it is one of the few Jewish ritual objects about which there are detailed prescriptions for how its “biography” ought to unfold. Rules lay out how a Torah Scroll should be crafted, and how it should be treated during its lifetime. So, too, there are rules to determine when a Torah Scroll has reached the end of its life and how it should be disposed of. The new phenomena of “Holocaust Torahs” overrides these guidelines, raising ethical and spiritual questions about the purpose of Torah Scrolls and how they ought to be treated. We will address this during the first half hour of our upcoming class

This story, found here, focuses on the how the windows’ biography unfolded once the congregation that owned them shrunk, and finally ceased to operate.

This very interesting piece helps to tease out the different ways of valuing stained glass windows. In some ways they are simply commodities. In other ways, they represent the soul of a building (and perhaps the soul of the congregation itself). |

alanna e. cooperOur Communities, Our Stuff Archives

May 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed