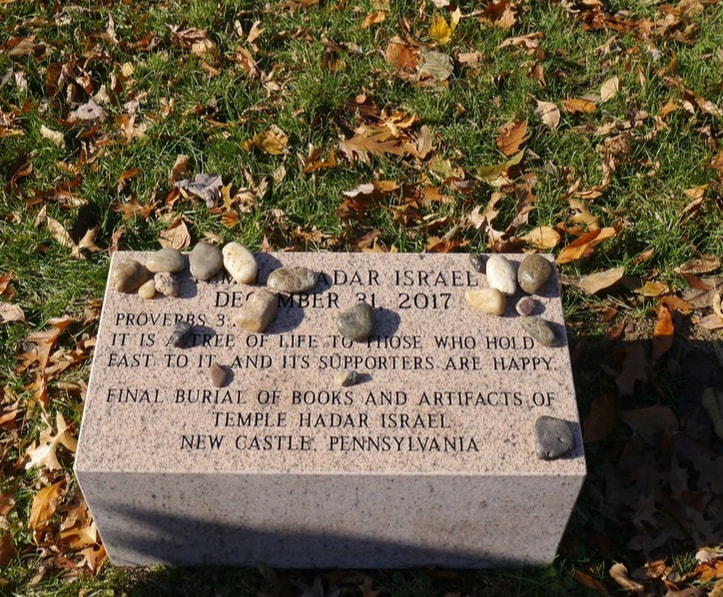

| | Almost one year ago, members of Temple Hadar Israel closed the doors of their building, disbanded, and held a burial service for the sacred objects that they were not able to pass on to others. (I published a story about that event here). This past Sunday, I attended the unveiling, where a modest salisbury pink granite gravestone was revealed. Each of those gathered for the short service placed a stone upon the etched words, which read, “Final burial of books and artifacts of Temple Hadar Israel.” |

During the years and months that the congregation carefully and deliberately prepared for their synagogue’s closing, they worked hard to find new homes for their ceremonial possessions. Their ten Torah scrolls were donated to congregations across the world. Many of the yahrtzeit plaques were given to family members of the deceased. And the magnificent Lions of Judah sculpture that once stood above their Holy Ark was given to Congregation B’nai Abraham in Butler, Pennsylvania, which raised funds to refurbish the historic piece, and mount it in their sanctuary. Today, the lions watch over B’nai Abraham congregants, reminding them that they are now part of New Castle’s Jewish legacy.

Despite efforts to find new owners for all their community items, the closing down of many small congregations across the rust belt, combined with a general glut of material culture, has meant that new homes could not be found for everything. Some books, prayer shawls, dedicatory plaques, and yahrtzeit plaques were simply orphaned. Rather than throwing these out, the congregation took solace from the Jewish tradition of burial, as a respectful way to dispose of honored, sacred items.

While burial of holy books is a prevalent Jewish practice, installing a gravestone to mark the spot, and holding an unveiling for it is not. Rabbi Howard Stein who conducted the service in New Castle, and Sam Berstine, who served as the congregation’s last president and who organized the service, both told me that they had never heard of any synagogue holding such an event. But it offered the group a sense of closure. “We hold unveilings for our parents who are buried here in this cemetery, we thought we should do it for our congregation as well. We did it out of respect," Bernstine explained.

The event was also a way to gather together the city’s few Jews – many of whom have joined other congregations in Youngstown and Pittsburgh – who no longer have a regular opportunity to meet. With quivering lips, and a tissue to catch her tears, Sybil Epstein, one of the elders who grew up in New Castle, explained, “When we are gone, and people come here to the cemetery to visit their ancestors, they will see this marker here. And they will know that we were a group that really cared, and mattered.”

Despite efforts to find new owners for all their community items, the closing down of many small congregations across the rust belt, combined with a general glut of material culture, has meant that new homes could not be found for everything. Some books, prayer shawls, dedicatory plaques, and yahrtzeit plaques were simply orphaned. Rather than throwing these out, the congregation took solace from the Jewish tradition of burial, as a respectful way to dispose of honored, sacred items.

While burial of holy books is a prevalent Jewish practice, installing a gravestone to mark the spot, and holding an unveiling for it is not. Rabbi Howard Stein who conducted the service in New Castle, and Sam Berstine, who served as the congregation’s last president and who organized the service, both told me that they had never heard of any synagogue holding such an event. But it offered the group a sense of closure. “We hold unveilings for our parents who are buried here in this cemetery, we thought we should do it for our congregation as well. We did it out of respect," Bernstine explained.

The event was also a way to gather together the city’s few Jews – many of whom have joined other congregations in Youngstown and Pittsburgh – who no longer have a regular opportunity to meet. With quivering lips, and a tissue to catch her tears, Sybil Epstein, one of the elders who grew up in New Castle, explained, “When we are gone, and people come here to the cemetery to visit their ancestors, they will see this marker here. And they will know that we were a group that really cared, and mattered.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed