I saw the film as part of the Israeli documentary series that CWRU-Siegal is co-sponsoring with the Maltz Museum this semester to accompany its exhibit, "Israel Then and Now." From the opening conversation between 96-year-old Miriam Weissenstein and her charming grandson Ben, the film entices.

Sitting in their Tel Aviv photo shop, Ben berates Miriam for talking about two customers while they were in ear-shot. As though speaking with a child, he reminds his grandmother not to say nasty things about people aloud, particularly when she is not wearing hearing aids. “Everyone can hear you, Grandma,” he tells her, “Except yourself!”

Miriam shrugs off the criticism. "Well” she inquires about the customers, “did they end up buying anything?” They did not, Ben explains, they were just browsing. “So you see,” Miriam counters, “they really are just pests!”

So many of the shop’s visitors browse without purchasing, it is easy to forgive Grandma Miriam for referring to them as pests. The cramped space where she and Ben spend their days, serves mostly as a sort of museum, offering an archive and permanent display of photographs shot by Miriam’s famous husband, Rudi Weissenstein (1910-1992).

Sitting in their Tel Aviv photo shop, Ben berates Miriam for talking about two customers while they were in ear-shot. As though speaking with a child, he reminds his grandmother not to say nasty things about people aloud, particularly when she is not wearing hearing aids. “Everyone can hear you, Grandma,” he tells her, “Except yourself!”

Miriam shrugs off the criticism. "Well” she inquires about the customers, “did they end up buying anything?” They did not, Ben explains, they were just browsing. “So you see,” Miriam counters, “they really are just pests!”

So many of the shop’s visitors browse without purchasing, it is easy to forgive Grandma Miriam for referring to them as pests. The cramped space where she and Ben spend their days, serves mostly as a sort of museum, offering an archive and permanent display of photographs shot by Miriam’s famous husband, Rudi Weissenstein (1910-1992).

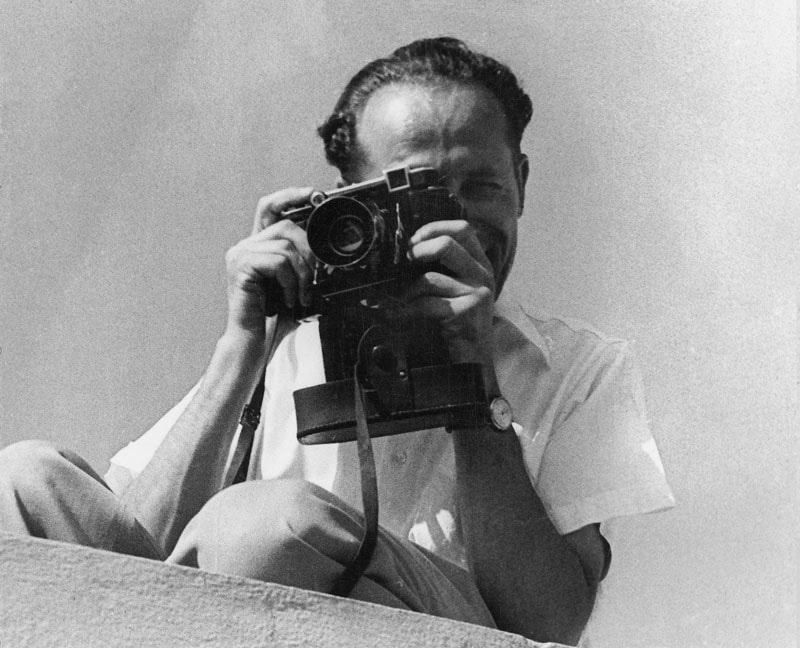

| Born in Czechoslovakia, Rudi immigrated to Tel Aviv a few years before Israel's independence after studying photography and the arts in Vienna. A Zionist, he had a particular interest in documenting the young state’s growth and development. He took sharp, stylized photos of street scenes, beaches, and kibbutz life, and also captured important historical events. Among the most famous are Rudi’s iconic photos of David Ben Gurion reading Israel’s Declaration of Independence, |

as well as his portraits of the state's formative leaders including Ariel Sharon, Moshe Dayan, Golda Meir, and Shimon Peres.

Life in Stills toggles between Rudi’s black and white photos of Israel in the early days - when today’s old buildings were new, and the people looked younger, and full of optimism - and images of the cramped, languishing Photo House in present-day Tel Aviv. The story pivots on an eviction notice, a precursor to the construction of a new block of buildings to be developed in the run-down corner of the city where the Photo House is located.

With three months to pack up a life’s worth of work, Ben asks his grandmother if she has the strength. Tired, weak and heartbroken from a family tragedy, Miriam answers with a matterof-fact “No.”

Against the backdrop of Rudi’s crisp historic photos and gritty contemporary Tel Aviv street scenes, the viewer is permitted into the tender and complicated relationship between grandmother and grandson. Suffering in two very different ways from the same traumatic loss of Ben’s mother – and Miriam’s daughter – pain’s narcissism lodges between them. Yet, the pair cling to one another with a love that is deep and pure. “You calm me down, Grandma,” Ben sighs, as he drifts off to sleep beside her.

Spend a few dollars on Amazon.com, and you can find out where Weissenstein’s Photo House ends up, so I won’t spoil the end.

As for the recent screening at the Maltz - I was intrigued by the comments Daniel Levin offered from the podium at the film’s end. A professor of communication and design and accomplished photographer himself, Levin analyzed the strengths of Rudi Weissenstein’s work, drawing on a stunning set of photos. In light of the film’s focus on loss, Levin also cautioned audience members vigilance in tending to their own photos, which serve as important repositories of the past. In this era of digital media, he urged the audience to make prints, and to back up their files.

Photos, of course, are not the only things that are vulnerable to loss. Life in Stills shows that urban landscapes are constantly shifting. Our buildings themselves, which hold stories of the past, may be here one day and gone the next.

If there is any moral to the story it is that our photos and built environments may disintegrate, but the past endures in our relationships with those we love and hold close.

Life in Stills toggles between Rudi’s black and white photos of Israel in the early days - when today’s old buildings were new, and the people looked younger, and full of optimism - and images of the cramped, languishing Photo House in present-day Tel Aviv. The story pivots on an eviction notice, a precursor to the construction of a new block of buildings to be developed in the run-down corner of the city where the Photo House is located.

With three months to pack up a life’s worth of work, Ben asks his grandmother if she has the strength. Tired, weak and heartbroken from a family tragedy, Miriam answers with a matterof-fact “No.”

Against the backdrop of Rudi’s crisp historic photos and gritty contemporary Tel Aviv street scenes, the viewer is permitted into the tender and complicated relationship between grandmother and grandson. Suffering in two very different ways from the same traumatic loss of Ben’s mother – and Miriam’s daughter – pain’s narcissism lodges between them. Yet, the pair cling to one another with a love that is deep and pure. “You calm me down, Grandma,” Ben sighs, as he drifts off to sleep beside her.

Spend a few dollars on Amazon.com, and you can find out where Weissenstein’s Photo House ends up, so I won’t spoil the end.

As for the recent screening at the Maltz - I was intrigued by the comments Daniel Levin offered from the podium at the film’s end. A professor of communication and design and accomplished photographer himself, Levin analyzed the strengths of Rudi Weissenstein’s work, drawing on a stunning set of photos. In light of the film’s focus on loss, Levin also cautioned audience members vigilance in tending to their own photos, which serve as important repositories of the past. In this era of digital media, he urged the audience to make prints, and to back up their files.

Photos, of course, are not the only things that are vulnerable to loss. Life in Stills shows that urban landscapes are constantly shifting. Our buildings themselves, which hold stories of the past, may be here one day and gone the next.

If there is any moral to the story it is that our photos and built environments may disintegrate, but the past endures in our relationships with those we love and hold close.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed