“Circumcise the foreskin of your heart.” What can this verse from the Torah possibly mean? I won’t answer that here. I’m interested, instead, in knowledge theory. By that, I mean: How should one go about figuring out what this Biblical verse means?

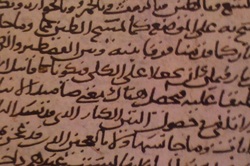

Let’s consider this issue through the eyes of a hypothetical, Reuven, who lived in 9th century Baghdad. Reuven found himself perplexed by the notion that a heart has a foreskin, and wondering about how one might go about circumcising that foreskin. What might he have done to find answers to his questions? That depends, of course, on the sort of relationship he had with the text of the Torah.

If Reuven traveled in Rabbinate circles, he would have turned to the religious authorities of his day for answers to his questions. “Rabbi Yehoshua,” he might ask, “the Torah commands us to circumcise our hearts. What does this mean?” Rabbi Yehoshua would frame his answer in terms of the knowledge and understanding that he had received from his teachers, who in turn would have received this from the generations of teachers who came before them. The central text around which this chain of tradition would have been transmitted was the Talmud.

If—by contrast--Reuven traveled in Karaite circles, finding answers would have taken a very different course. For if he had turned to an erudite Karaite scholar with his questions, he probably would not have received an answer. Instead, he would have been met by reprimand. “Search ye well in the Torah, and do not rely on my opinion.”

Reuven--it seems--would have been on his own. He would not have had the Talmud to turn to for answers, for Karaite authorities decried the authority of that text. He also would have been bereft of contemporary figures of religious authority. Karaite creed valorized an unmediated relationship to the text. Each individual was enjoined to read it on his own, and to reach his own understanding of its meaning and its practical implications. In the words of ninth century Karaite Al-Kumisi “he who relies on any of the teachers of the dispersion and does not use his own understanding is like him that practices heathen worship.”

Al-Kumisi’s approach was re-articulated in the fifteenth century text, Aderet Eliyahu. Outlining some of the basic principles of Karaite Judaism, author Elijah Bashyatchi wrote:

1. The physical world was created.

2. It was created by a Creator who did not create Himself, but is eternal.

3. The Creator has no likeness and is unique in all respects.

4. He sent the prophet Moses.

5. He sent, along with Moses, His perfect Torah.

6. It is the duty of the believer to understand the original language of the Torah.

The chain of transmission as outlined here is clear and succinct: God gave the Torah to Moses. The Torah, in turn, was given to each and every individual in its pure, unadulterated and perfect form. The text is open and accessible to all. It requires no mediator, and it is the duty of the believer to study it (in the original of course – not through any one else’s translation), to gain an understanding of it, and to figure out how it should be applied.

Contrast this map of transmission to that which is written in the Rabbinic text, Mishna Avot: Moses received the Torah from Sinai and transmitted it Joshua. Joshua transmitted it to the Elders, the Elders to the Prophets, and the Prophets transmitted it to the Men of the Great Assembly. They [the Men of the Great Assembly] said three things: Be deliberate in judgment, raise many students, and make a protective fence for the Torah.

According to this theory of knowledge, if an individual wishes to know what the Torah means, that individual must first recognize that he cannot sit alone with the text. To understand it, he must enter a study-house that is occupied by authorities; those who are versed in the teachings of the generations of scholars who preceded them. These authorities’ readings must, in turn, be refracted through the authoritative knowledge of those who studied before them, and those before them. In this scenario, the individual’s relationship with the text is anything but unmediated.

This difference between the Rabbinites and the Karaites that I’ve portrayed here is a caricature-like depiction. How could Karaites not have any norms, authority figures, teachers, leaders, and texts through which the Torah is mediated? Likewise, how could the Rabbnites have no allowance for personal, spontaneous, malleable readings of the text? Of course, neither scenario is possible in an unadulterated form.

Yet, the contrast provides a very compelling heuristic; a way of allowing us to think about religious knowledge theory. What is the place of religious authority and tradition on on the one hand, and the place of personal autonomy and meaning on the other? I struggle with these questions in my religious life every day.

Let’s consider this issue through the eyes of a hypothetical, Reuven, who lived in 9th century Baghdad. Reuven found himself perplexed by the notion that a heart has a foreskin, and wondering about how one might go about circumcising that foreskin. What might he have done to find answers to his questions? That depends, of course, on the sort of relationship he had with the text of the Torah.

If Reuven traveled in Rabbinate circles, he would have turned to the religious authorities of his day for answers to his questions. “Rabbi Yehoshua,” he might ask, “the Torah commands us to circumcise our hearts. What does this mean?” Rabbi Yehoshua would frame his answer in terms of the knowledge and understanding that he had received from his teachers, who in turn would have received this from the generations of teachers who came before them. The central text around which this chain of tradition would have been transmitted was the Talmud.

If—by contrast--Reuven traveled in Karaite circles, finding answers would have taken a very different course. For if he had turned to an erudite Karaite scholar with his questions, he probably would not have received an answer. Instead, he would have been met by reprimand. “Search ye well in the Torah, and do not rely on my opinion.”

Reuven--it seems--would have been on his own. He would not have had the Talmud to turn to for answers, for Karaite authorities decried the authority of that text. He also would have been bereft of contemporary figures of religious authority. Karaite creed valorized an unmediated relationship to the text. Each individual was enjoined to read it on his own, and to reach his own understanding of its meaning and its practical implications. In the words of ninth century Karaite Al-Kumisi “he who relies on any of the teachers of the dispersion and does not use his own understanding is like him that practices heathen worship.”

Al-Kumisi’s approach was re-articulated in the fifteenth century text, Aderet Eliyahu. Outlining some of the basic principles of Karaite Judaism, author Elijah Bashyatchi wrote:

1. The physical world was created.

2. It was created by a Creator who did not create Himself, but is eternal.

3. The Creator has no likeness and is unique in all respects.

4. He sent the prophet Moses.

5. He sent, along with Moses, His perfect Torah.

6. It is the duty of the believer to understand the original language of the Torah.

The chain of transmission as outlined here is clear and succinct: God gave the Torah to Moses. The Torah, in turn, was given to each and every individual in its pure, unadulterated and perfect form. The text is open and accessible to all. It requires no mediator, and it is the duty of the believer to study it (in the original of course – not through any one else’s translation), to gain an understanding of it, and to figure out how it should be applied.

Contrast this map of transmission to that which is written in the Rabbinic text, Mishna Avot: Moses received the Torah from Sinai and transmitted it Joshua. Joshua transmitted it to the Elders, the Elders to the Prophets, and the Prophets transmitted it to the Men of the Great Assembly. They [the Men of the Great Assembly] said three things: Be deliberate in judgment, raise many students, and make a protective fence for the Torah.

According to this theory of knowledge, if an individual wishes to know what the Torah means, that individual must first recognize that he cannot sit alone with the text. To understand it, he must enter a study-house that is occupied by authorities; those who are versed in the teachings of the generations of scholars who preceded them. These authorities’ readings must, in turn, be refracted through the authoritative knowledge of those who studied before them, and those before them. In this scenario, the individual’s relationship with the text is anything but unmediated.

This difference between the Rabbinites and the Karaites that I’ve portrayed here is a caricature-like depiction. How could Karaites not have any norms, authority figures, teachers, leaders, and texts through which the Torah is mediated? Likewise, how could the Rabbnites have no allowance for personal, spontaneous, malleable readings of the text? Of course, neither scenario is possible in an unadulterated form.

Yet, the contrast provides a very compelling heuristic; a way of allowing us to think about religious knowledge theory. What is the place of religious authority and tradition on on the one hand, and the place of personal autonomy and meaning on the other? I struggle with these questions in my religious life every day.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed